What should we call the discipline in between life science and engineering?

I was trained in a lab that called it synthetic biology. I went to conferences with synthetic biology in their name, joining up with other labs from around the world that also called it synthetic biology, participating in various consortia, journals, events, and grants that all used the same term.

Why “synthetic biology”? The best answer I’ve heard from one of the people involved in the very earliest days was, “well, bioengineering was taken.”

There were other communities that called what they did bioengineering, or metabolic engineering, or genetic engineering, industrial biotechnology, or any of a number of other combinations of bio and technology words. Calling it something else defined it as a new community with subtly different kinds of approaches and principles and values. This was a new community founded primarily by engineers, who sought to imbue biology with “real” engineering principles.

From the beginning, the engineering focus and oxymoronic character of the term sparked intense passions and spawned further paradoxes. From its ability to capture attention—and therefore grant funding—there was a sense from outsiders that synthetic biology was too good at branding. It’s “just” good marketing that defines synthetic biology and brings everything under its umbrella; that money should go to more deserving and more precisely named fields!

But many argued that it was also terrible branding. Everyone knows that people hate things that are “synthetic” — the name was obviously going to turn consumers further against genetic engineering than they already were!

Amidst this opportunity and confusion, other (re)branding efforts emerged. A decade ago as synthetic biology businesses were growing and debates about whether and how to label GMO ingredients in foods raged, new brands were born to highlight the different values and priorities of the technology and its potential products: precision fermentation, predictive biology, intentional biology, biodesign, biofabrication, techbio, etc, etc.

“Bioengineered” won the labeling wars, and around the same time, the academic research consortia rebranded away from synthetic biology to “engineering biology,” self-consciously trying to avoid the stigma of “synthetic” and GMO.

Today, not many people call themselves synthetic biologists, debates continue about whether “techbio” is cringe, and the academic groups formerly known as synthetic biology research centers are still trying to make Engineering Biology happen. A recent brand awareness survey of 3000 UK residents (see Titus’s post over at the Connected Ideas Project for an in-depth reflection on the study and its results) shows how all of this has played out in the minds of the average consumer.

The study asked, "have you ever heard of the term engineering biology?” Unsurprisingly (to me at least!) more than 60% had never heard the term at all, while only 2% said they could explain what it means in detail.

Should engineers of biology worry that their particular niche brand name for their flavor of biology + technology has low awareness among the general public? Of course not. Especially because of what the rest of the study revealed: after explaining to respondents that engineering biology is an approach to using cells for making things like medicine and biodegradable materials, more than 80% said that engineering biology was fairly or very useful for food, medicine, chemicals, and waste recycling. What’s more, the same proportion was fairly or very comfortable with the use of the technology in those same domains, as long as it was shown to be safe, effective, and sold at a good price.

The names of these disciplines has clearly meant a lot to practitioners, who see the subtleties and distinctions that shape where they put themselves relative to the boundaries between them. But to anyone outside of those communities, what matters isn’t what you call yourself, it is what you do. A brand is more than its name and logo.

A great brand defines a problem and sparks a movement. A new name makes a space for people to meet and get to work. People connect under this new banner, exchanging ideas and perspectives towards solving the problem.

In the early days of synthetic biology, an undisciplined and broadly ambitious movement came together of people who agreed that biology was too hard to engineer. What mattered wasn’t defining the field “correctly”, but making the field broad enough for different approaches to meaningfully come together. As Kristala Prather shared in a 2009 article ironically surveying 20 practitioners for their definition of the term: “if you ask five people to define synthetic biology, you will get six answers.”

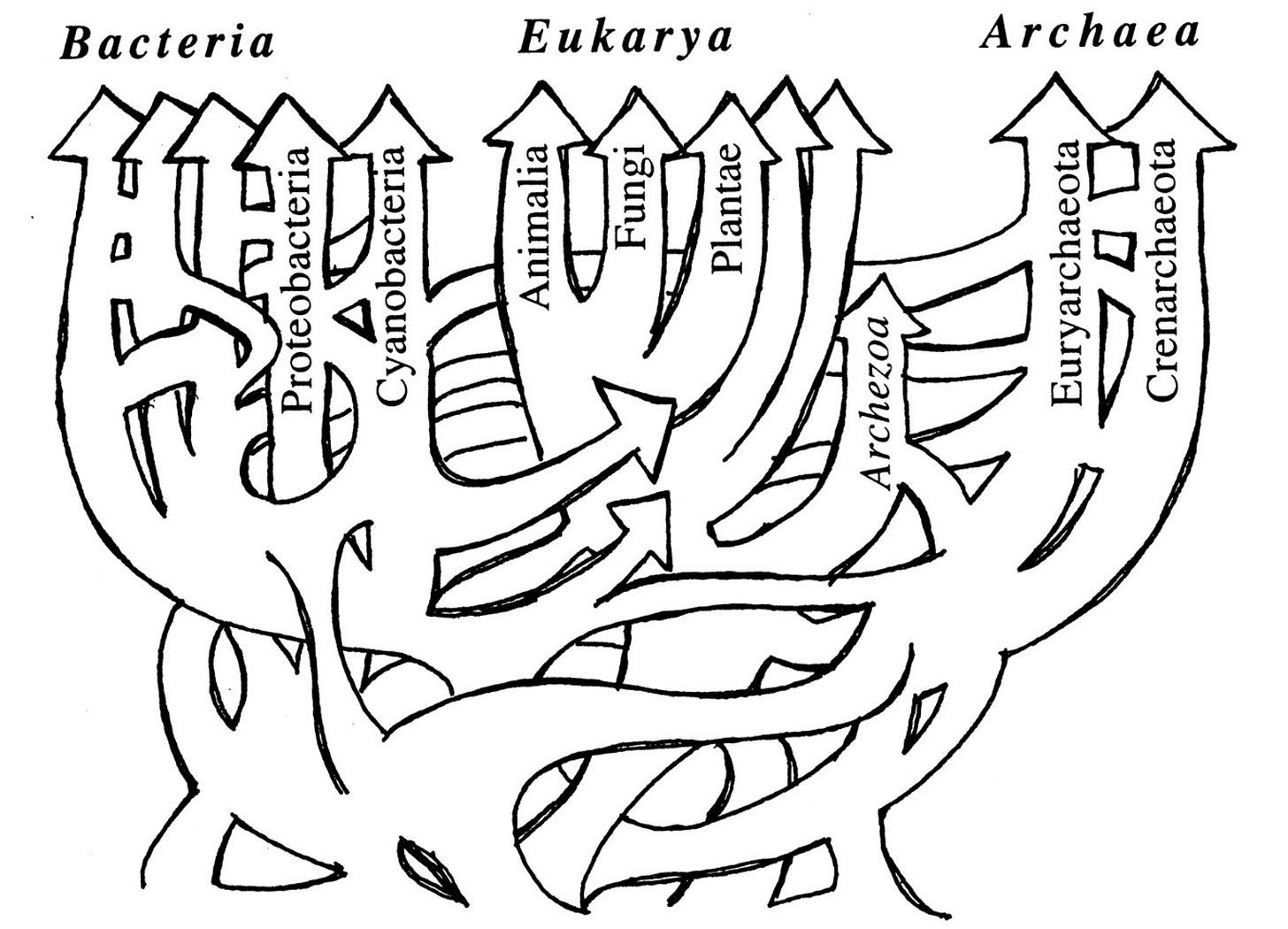

Perhaps this problem is uniquely biological. Evelyn Fox Keller tackles the question of “what biologists want” in her book Making Sense of Life. While physicists might all at some level be seeking a unified theory of everything, she argues, there are as diverse a number of ways of making sense of life (and making biology easier to engineer) as there are living things, and living biologists. And like living things, technologies, brands, and disciplines aren’t static. They are ecosystems that shift and change as people enter and exit. They grow, divide, share, steal, recombine, die.

So what comes after synthetic biology? Today, AI is likely the most unifying movement in terms of tools and collective fantasies, with ideas about superintelligence rallying adherents and frustrating critics who want more precise definitions and concrete predictions. At the same time, the diversity of potential applications has meant that synthetic biology is evolving into a wide range of different products and industries that are no longer defined by academic lineage of their original designers. As my friends over at Ferment wrote in a recent blog post:

Our goal is to see the end of industrial biotechnology as a siloed sector, because biology will simply be part of the reality of how new products are developed and how problems are solved. We envision a future where biology is ubiquitous, not exceptional.

And after synthetic biology, there will also continue to be new biologists and new physicists, engineers, and computer scientists who will meet each other and decide that biology needs new tools and new paradigms, new ways of making living technologies. They’ll call themselves something different and they’ll make new, exceptional things.

This is so full of little unique historical bits. Only someone who has helped build the field and the stories we tell of it would be able to connect these points together, Christina. It is really fantastic to get your perspective on writing.

I think a good bit — but not all — of the nomenclature treadmill comes from academia’s quest for novelty. And its easier to manufacture the perception of novelty than it is to find the real thing. Of course, the same fashions exist in industry and in all people. But I think academia feels the pressures to deliver novelty the most.